All Welcome to the upcoming Symposium on Genre Painting in the Sybil Connolly Lecture Theatre at NCAD next Friday 19th January at 11 am.

All Welcome to the upcoming Symposium on Genre Painting in the Sybil Connolly Lecture Theatre at NCAD next Friday 19th January at 11 am.

The following is a transcript of a conversation between Damien Flood and Madeleine Moore at Damien Flood’s exhibition, A Root that Turns as the Sun Turns, at the Green on Red Gallery, Dublin, in November 2016. It coincided with a visit by second year painting students as part of their Professional Practice module.

Damien Flood, A Root that Turns as the Sun Turns, Green on Red Gallery, Installation shot

MM: You were on the MFA course at NCAD from 2006-2007. What has happened since then?

DF: To start the story correctly, I need to go back a little further as I started off as a representational painter. I started being obsessed with painting from around the age of 16. When I decided to go to college, I gave up a lot of ideas I had built up about painting. In many ways this gave me a clean slate. I undertook my BA in Dun Laoghaire between, 1999-2003, at this time they were very much pushing conceptual art, pushing for 3D and 4D, as they called it. I was interested in the ideas, but for me the medium didn’t resonate with me. I finished up my BA making small representational paintings. They were copied images from newspapers. Every day I would collect the daily newspapers and copy an image I found interesting.

When I left college I became quite disheartened with these paintings I’d made. I started working in a bank in Greystones and a few weeks into the job they where hosting the AIB Photography prize for newspaper photographs. 90% of the photographs in there were ones I had chosen for my BA show. It was a shattering of my ideas at the time. Someone else had clearly spent a lot of time taking these photographs and left me wondering what I was adding to them, which I couldn’t honestly answer.

Shortly after this I met up with a friend from college and we became interested in the bones of painting. How traditional paintings where made and what where the techniques they used. For me it was time off from any sort of conceptual ideas and actually just start researching how to paint in a renaissance and baroque manner. So I spent the next two/three years doing that down in Wicklow. Working out how to make paintings in a more traditional way. Me and made friend made around five life size copies of the Last Supper. Mainly because we had a fantastic book that contained pigment samples and cross sections of the plaster, although it must be said we where using oil on canvas. I think the whole exercise was about technique and tone in the end. That brought me up to 2006 where I hit another road block. I’d started introducing slightly more conceptual ideas to my now renaissance slanted paintings. They were kind of bad John Curran copies, they weren’t good at all.

So in late 2006 I went back to do an MA at NCAD as a last ditch effort, trying to find something in painting that worked for me. At that time as well, I realised I was more interested in what was happening on the palette, how the paint was mixing, how the images where constructed through colour and tone.

The MA gave me two years to sit down and think it through, bounce ideas off my peers and have these ideas challenged. In the first year of the MA I completely deconstructed everything and picked my practice apart. I sat with a giant piece of paper using thought bubbles to try and find out what I was interested in. And then the scariest thing happened in my second year of MA, when I stopped painting altogether and made some really bad installations. I tried experimenting with lots of different installations. They were terrible but necessary. I think they gave me space away from painting to readdress my relationship with the medium.

During this time I hit on an interesting area, I discovered some beautiful drawings that came from the HMS Challenger which was a 17th Century Darwinist voyage, when people were going out and discovering new territories for the first time. This resonated with me, discovering something new, the unknown, the uncanny. There was something in it for me that opened up this idea in painting where I could start to create my own world and try to create that sense of mystery and questioning. The thing that has continued on from then to now is to ask questions with the work, that the work isn’t passive, that it asks you a question rather than giving an answer. I think a lot of art in the past tried to give answers to big questions but I just prefer to ask questions about what’s happening on the canvas and in my life. What is the relationship between certain objects and how they relate back to the world around us, personally or emotionally. It’s also worth noting as well that when I hit on these ideas it started to link my interest in the mechanics of painting and this kind of language, the pure language of painting. Using the paint to do the work on the canvas and not illustrate the idea. It also began to play with the notion of how as humans we want to be told a story. This interest in narrative began alongside these ideas.

I remember on the MA there was a guy who was making video art. He said to me that he wanted to make video art with no narrative. I was just blown away by this. My only response to him was, ‘Good Luck.’ (Laughs). We want to be told stories, we all look for stories. It’s the power of abstract painting in a way that you can put down these seemingly irrelevant parts to each other and the human brain will try and connect them. What I try to do in my work falls somewhere in between that, where you are putting down snippets of information or shapes that begin to become something that stop on a knife edge, that don’t fully form themselves into anything. You have this area, I guess it’s a grey area, where the viewer gets to project their own thoughts into or you start to piece together these snippets of other information.

MM: And after you left NCAD you were selected for the John Moores exhibition weren’t you?

DF: Yes, I was lucky enough to be selected in 2008 with a small painting from my MFA. It was a good sign that I was on the right track. I was also selected again in 2010.

MM: So your works at that time would have been much smaller in scale than these?

DF: Yes – intimate scale was the term used for them! This was for a number of reasons. I was only starting to carve out a new area so it was very practical, I could cover a large area of canvas quite quickly and could get through the process quicker, work out the thought. Also, I’m an intuitive painter. There are no sketches or preliminary drawings or preliminary paintings for any of these works. Everything you see on the canvas is what happened when it happened. There’s a lot of sitting and wondering what the next mark will be but there are no sketches done. I’ve always worked that way and that was one of the reasons why working small scale during the MFA and for a few years after that was important, there’s less time to think. When you go to put down a wash of red, you get the whole thing covered in less than a minute. When you’re working at this scale (Parting, 180 x 140) there was an awful lot of time to think from beginning to end, where you start questioning, ‘is this the right grey? What am I going to put on this?’ and it can interrupt your thought process.

MM: Is that the physical mechanism of larger painting?

DF: I was quite a good representational painter. So when I would paint small it was all about the delicacy of the wrist, you could do these beautiful marks. When you scale up, the wrist becomes the elbow. Becomes the shoulder. To try and keep that tactile nature of the paint in larger brushstrokes is a different challenge.

MM: You say you don’t work from drawings. How do you know where to put things? How do shapes evolve? How does space happen?

DF: There is research done for my work. Two shows ago I had three trips to Dubai and the second one was a full research trip spending two weeks exploring. After such a research trip I go back into the studio and there’s an archaeological dig back through my mind of what resonated with me. This is done on the canvas, as it’s happening certain tones and shapes begin to form and link up. Painting is one of these beautiful mediums that connects so well with our emotions. So, when you go to paint, if you feel something about a place, that comes out on the canvas. With Dubai, there was the sky and the desert and the people, the rhythm of the place, the movements in the architecture, the people’s gestures, would all resonate through in the paintings. While painting, these motifs and ideas would start to arrive.

The work in this show was created in a similar way. These paintings are quite closely related to the last show I had which was in the Lexicon in Dun Laoghaire. That show was very much to do with the people of Dun Laoghaire. For that show I went and interviewed people from the area and asked them about Dun Laoghaire on a personal level. In Dubai, I was a stranger so everything was amazing – the smells, the noises. There was a beautiful thing as well being in a place for no reason apart from researching a show, it’s the strangest experience. In Dun Laoghaire there was the challenge of ‘well I know Dun Laoghaire really well.’ But I didn’t know any of it’s history or any of its community so talking to people brought up a lot of interesting ideas. I got to see it through their eyes to a degree. The problem with that research for me was that this work was very much connected to the community, so that posed a problem for me, there were more people at the party. Normally it’s just a two-person party, just me and the canvas. Suddenly there were all these other voices clamouring in around me. It was quite tough. I also felt that I had to do good by them -they had spent all this time talking to me. It posed a lot of problems. When this show came along I got the chance to go fully personal. This show deals a lot with our relationships and our mortality.

MM: In relation to painting having a daily studio practice, and there being opportunities to respond to as artists which might have a community or social dimension, was the Dun Laoghaire residency a proposal that you made to develop your practice in a direction that responded to place and people?

DF: When the opportunity came up it was natural to go from the Dubai show. Before that my research would have been done through books and reading. This seemed like an opportunity to challenge myself and get out there and meet people. Studio practice for a painter, it’s just you and four walls.

MM: Do think colour carries an association to place? Would you want us to make connections between these paintings and a particular place?

DF: With this body of work I doubt that would happen. These works are quite personal in a way. I actually went through grief counselling and a lot of these works have to do with that. Five months of sitting and talking to someone, it’s actually a beautiful thing to be able to do, to actually sit here and talk to someone and not be judged. It brought up a lot of different ideas and spaces and places. There was this decision, ‘do I let that out into the work?’ and it actually became a non-decision. As my practice has grown and I’ve become more confident in what I do, there is less of a barrier between me and the work. Before, when I left my MFA, I would have done stuff by the book. I would do my ‘research’ and everything was how you were taught to do it. But as you continue on into your own practice, you make some changes. That barrier between the personal and the work begins to corrode away.

MM: The counselling. The work doesn’t feel dark.

DF: There’s nothing dark about it. I remember the second session of counselling, feeling this weight being lifted. My mum passed away very suddenly from cancer and then my dad got diagnosed with cancer. During the summer I was driving my dad in and out of Saint Luke’s while undergoing grief counselling myself. The trips in and out of the hospital where actually quite a nice bonding experience, it was just me and him sitting in the car on this journey. I selected music from my childhood to accompany us on the journey. The music seemed to trigger different stories from our past, some I’d never heard before. These paintings connect up to these journeys and stories and counselling. So none of it is dark. Mortality is the strangest thing in the universe, we all think we have some understanding of why we are here and what everything is about but we really don’t.

MM: How do you decide on the size of the canvas?

DF: What can fit in the studio. I draw sizes on the wall to work out what they’re going to look like and feel. Most of my work is done in portrait format which creates a humanistic element to it. I haven’t done many landscape paintings in the last few years but they are beginning to creep back in.

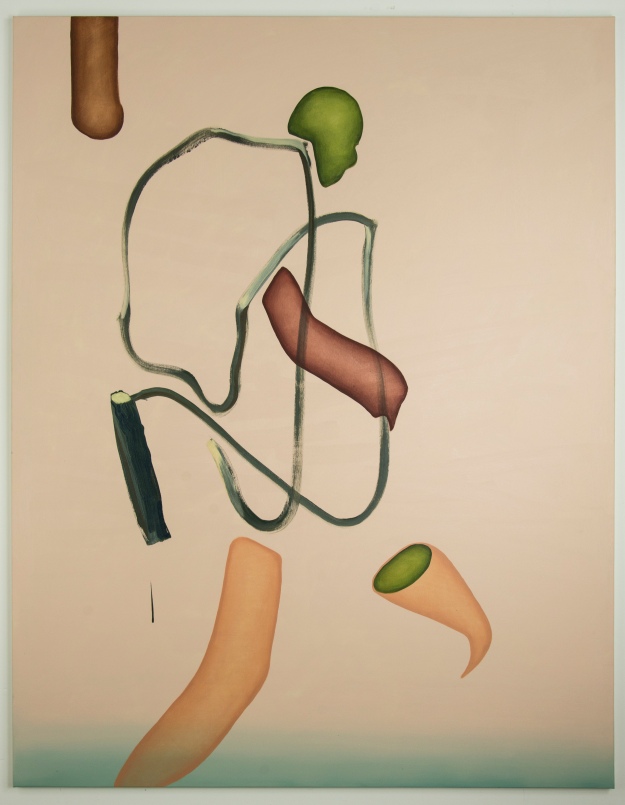

Simple Game 2016, Oil on canvas, 180 x 140 cm

Simple Game 2016, Oil on canvas, 180 x 140 cm

MM: The colour is quite fleshy.

DF: Yes, there’s a lot of fleshy tones in the work. I think they are a direct reference to skin, mortality and fragility.

Some questions were then asked by the NCAD second year painting students.

Q: Do you look to other artists?

DF: At the moment, no. There’s artists I like and keep an eye on, I tend not to look as much when I’m making. This year has been very busy. My brain is a sponge- all painters are thieves and there’s nothing wrong with that. Even in Dublin we’re all stealing each others work- little bits here and there. When I’m making I’m focusing that bit more- for me when I’m making it’s a very delicate time in terms of what I see and listen to. Big influences would be Norbert Schwontkowski and Tala Mandani. She’s one of the most exciting painters at the moment. Ivan Seal’s a fantastic painter. I’m really interested in the way people apply paint. Tala Mandani is like a punk rock painter. Her stuff is very political but I love how they operate on a purely painterly level while managing to stay political. She makes paintings that get into you, that jolt you a little bit.

Pear and Shadow, 2016, Oil on reversed black primed canvas

Pear and Shadow, 2016, Oil on reversed black primed canvas

Gift, 2016, Oil on reversed black primed canvas

MM: There’s a particular sense across all the work here of when enough is enough in the work. They are more held back than your earlier work.

DF: There has been a paring back over time. I’m interested in economical painting, pairing an idea or process back to it’s most simplest form. When paintings begin to ask questions, or when they are on the point of almost falling apart, that’s when they are interesting. How do you know when they are finished? They just say it, you just come in one day and there’s no more that can be added. From the first brushstroke you put down, you’re generally making the painting worse. You usually put down an amazing mark, and you think that’s brilliant if only that can be the painting, but it’s usually not interesting enough. Then you put down another one. It’s a kind of balancing act, it’s a game of chess. They’re about a reductive language, the least amount of information you can give to give the maximum amount of possible readings, less is more. It’s about stripping down this visual language, a lot of it does come from drawing. I was very obsessed with drawing early on and I love the power of the line. The line can inhabit so much. It can suggest spaces that aren’t there. We instantly believe drawing over painting. You can be shown a sketch of something and there is belief, whereas when you are shown a realist painting you think, ‘well it doesn’t really look real.’ You accept drawing more. I try and use that in the paintings and I try and keep them as simple and pared back as possible.

MM: People who do draw a lot, there’s always the question of how you translate that immediacy of the drawing into paint.

DF: That’s why I don’t do drawings for these (laughs).

MM: The actual painting becomes the drawing event, perhaps?

DF: Especially on the raw canvas ones, you can’t smudge anything out on them.

The problem is if you do a lovely drawing all that energy is expelled into that drawing. Then to start to try to put that on a canvas and it’s never the same because your eyes can’t be in two places at once. For me that’s a problem. Over the years I’ve refined this practice of putting on very very loud music and just getting the adrenaline going and just jumping in. There’s so much more going on in our subconscious that we don’t really understand and for me a lot of that comes out in the painting, trying to get to those areas. I don’t really know why I put down certain marks beside each other. You hear people talking about inspiration, inspiration is the other part of your brain kicking in. When you’re standing in front of a painting and you get this urge to put down some strange mark , you can’t quite explain where that comes from but that’s why you’re painting. If you’ve been painting for 15 or 20 years, there’s a lot of information stored up there. The thing that has to be said as well is that there’s no such thing as bad experiences when it comes to making art. You go and research something or you make some really bad installations, it all gets piled in, it all becomes an experience you can take from. Students before have asked me, ‘Should I experiment with different areas of video and sculpture?’ and I always answer ‘ Yeah, definitely, it’s all going to be valuable eventually. There’s no time wasted.’

‘When a Vienna museum guard befriends an enigmatic visitor, the grand Kunsthistorisches Art Museum becomes a mysterious crossroads which sparks explorations of their lives, the city, and the ways artworks reflect and shape the world.’

I highly recommend the film Museum Hours (2012), directed by Jem Cohen, with footage of the way we look at, visit and relate to paintings ( and the city) from the past in the present.

Posted by Madeleine Moore

The theme of November’s MFA Painting seminar was Jerry Saltz’s article on neo-mannerism, Art’s Insidious New Cliché, published in http://www.vulture.com .

Read the text here.

Saltz berates artists for producing an ‘ever-expanding assembly of anaemically boring artistic clichés squeezing the life out of the art world right now.’

The question for us was, is this the case? If so, is Salz’s argument limited to New York? As one of the comments on his post states, ‘maybe you are not looking in the right place.’

In reference to painting, Saltz states, ‘Nowadays we see endless arrays of decorous, medium-sized, handsome, harmless paintings. It’s rendered mainly in black, white, gray or, more recently, violet or blue. Much of it entails transfer techniques, silkscreening, stencilling, assemblage, collage, a little spray painting or scraping and the like. There might be some smooshy blocks of colour or stripes or other obvious open-form abstraction or geometric motif.’ He then goes on to say that much of the current work references mostly male painters like Albert Oehlen, Christopher Wool, Michael Krebber, Wade Guyton, Laura Owens and Sergej Jensen.

Here is a summary of the arguments that were made ‘for’ and ‘against’ Jerry in our seminar. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the painting department or of everyone at the seminar.

FOR

In support of Jerry’s argument, we looked at a painting by Chantal Joffe, ‘Walking’ which was described as ‘dispassionate,’ in comparison to Maria Lassnig’s work. We looked at Sarah Faux, Patrick Brennan and Zachary Keeting.

Another group of works were shown: Luc Tuymans, Daniel Richter, Damien Hirst, and Thomas Hirschorn. The argument around these works is that they were ‘cynical.’ For example, that Tuymans seeming ability to paint any historical figure, here Condoleezza Rice, in monochromatic tones has become a mannerism.

We looked at the blog structureandimagery.blogspot.ie, a contemporary art blog by Paul Behnke, which showed images of recent shows in Lower Manhattan and it was proposed that from the work shown, Saltz did have a valid criticism to make of current shows in New York.

AGAINST

Against Saltz’s argument, we looked at Scott Stack, Richard Roth and Tomma Abts, all influenced by artists such as Christopher Wool, mentioned in the article, but not falling into any neo-mannerist cliché, it was suggested. Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, seen in this year’s Turner Prize, was also cited as an artist whose work, at least, challenged the viewer’s assumptions about what contemporary figure painting could be.

Chris Martin’s work has many influences from music, literature and film. He paints large-scale canvases and ‘paints on records, slices of white bread, pillows, aluminium foil, and uses copious amounts of glitter- materials that seem immune to artspeak’. In a recent interview by Ross Simonini, he was asked, “What’s your definition of ‘bad’ or ‘unsuccessful’?”

CM: ‘Well, that’s a wonderful question, because as an artist it’s very interesting sometimes to say, I’ll try to make a bad one. And often the kind of energy around the bad one is actually great.’

We also showed a group of works from the ‘Invisible- Art about the unseen, 1957-2012’ exhibition that was held at the Hayward Galley in 2012. The works were Jeppe Hein’s Invisible Labyrinth, Yves Klein, in the void room, 1961, Tom Friedman, 1000 hours, and Tino Seghal. The argument here was that if mannerism was a result of too much, an excess, then these works would offer some relief. They are visually low-key works, which invoke invisibility to underscore and direct our attention towards the unwritten rules that shape our understanding of art. A contrast to Jerry’s ‘post- formalist formal arrangements of clunky stuff, sticks, planks, bent metal, wood boxes, fabric old furniture, concrete things and whatnot leaned, stacked, piled or dispersed around a clean white gallery.’

Jerry mentions Bjarne Melgaard at the beginning of the article and we examined his work. He works, sometimes collaboratively, on large-scale expressionistic paintings. His works are said to be created from ‘authentic impulses.’

We also looked at images from NCAD Painting department recent graduate, Sam Keogh,’s 2013 show at the Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, ‘Mop.’ The exhibition takes its premise from the character of Oscar the Grouch in the children’s television series Sesame Street, a character who collected dirty, messy and useless objects and whose presence in the programmes was to teach children to tolerate non-normative behaviours. The show consists of a vinyl floor covering, printed from Keogh’s drawings spliced together, spread across the entire floor of the gallery, on which are placed an array of images, sculptures and found objects. Although the presentation of the show ticks several of Saltz’s boxes, the way forms merge in and out of the background of the floor covering, and the way the viewer discovers the show over time and spends time with it and on it, the subtlety of the shifts in scale and consideration of detail and materials , all counteract Jerry’s argument.

Posted by Madeleine Moore

Common Ground was a collaborative project between Third Year students in the Painting Department at NCAD and Second Year Architecture students at the School of Architecture UCD, initiated by lecturers Madeleine Moore and Orla Murphy.

‘Common ground…a place of meeting from different positions’ – David Chipperfield, Curator Venice Biennale 2012

There were two sessions attended by both groups of students; one at UCD on Friday 9th November and one at NCAD on Friday 16th November. We visited the studios and workshops, and the students made group presentations of their studio methodology and practice, followed by a discussion.

The UCD group presented their proposals for a library or a civil ceremony building, for sites in Thomas Street and Smithfield. The focus of the project was the design of interior public space, and the spatial sequence from pavement to room.

The NCAD students presented work from their research project. This project involved intensively researching the area of interest for their practice, with a focus on ideas and finding source material, rather than on finished work. They watched a Screening of the film ‘Eames, The Architect and the Painter,’ (Jason Cohen and Bill Jersey, 2011). There was a Presentation by Madeleine in relation to types of Fine Art practices and where they share common ground with architectural practices including processes, places and places of display and ideologies.

Common areas of interest between us included: the recording of spaces and places; matter and space, archaeological methods of collecting and analysing fragments from sites; the representation of space and the materials and processes with which to do this; and the potential for future collaborations. And also locations: Thomas Street, with its sites and derelict buildings, and Smithfield, formerly one of the largest development sites in the city.

Staff: Madeleine Moore, Orla Murphy, Emmett Scanlon, Oliver Whelan

Here are some images from the session at UCD.

Posted by Madeleine Moore

‘Where Painting meets other Media’ was the theme for the second MFA Painting seminar held on 15 November. Students and staff contributed images of artists’ work, so it’s a selection, not a complete survey, and we had a lively discussion. We saw some new work, and revisited some more familiar works.

Wade Guyton and Dan Hays, whose paintings refer to print technology in differing ways. Hays work such as ‘Snow Effect,’ a large scale painting, where close-up, the surface of the image is broken down into dots, recalling pixels and inkjet printing. Wade Guyton, who scans fragments of images, works on them in simple programs such as Word, and then prints them onto canvas fed through an Epson Printer. The printing processes produces snags, blurs and streaks. Large works are made up of vertical panels, the width dictated by the maximum width produced by the printer.

We looked at ‘expanded painting’ including, Jessica Stockholder, Rachel Harrison and Isa Genzken. Harrison’s modes of display tend to be more chaotic- looking than Stockholder’s. When Stockholder uses objects they tend to retain less of a trace of their original function and to play a greater role in overall colour, shape and composition. In some of her work, the wall plays an important part in the work, as materials and objects are placed against it.

In Isa Genzken’s piece, Untitled, 2006, sofa (leather), goatskin, foam, plastic foil, mirror foil, plastic, fabric, lacquer, two knives, the object itself, the sofa, becomes a ‘canvas’, which is painted, whilst also having the other materials and objects attached to it. And Angela de la Cruz, whose works are viewed against the wall and as free-standing (also slouched, piled, and recumbant) objects, utilising the elements of a painted canvas itself- fabric, paint, timber stretcher bars, wedges and brackets.

Katharina Grosse and Michel Majerus both locate ‘painting’ within the gallery space. Majerus inserted paintings into white display structures, which connect them to the gallery space. The buttress- like structures connect floor plane to wall, frame windows, and also compel the viewer to step over them.

And using architecture as a subject matter, as in Lucy Williams’ meticulous bas relief collages from materials such as balsa wood, card, fabric and paper, which depict modernist architecture and interiors. They are painstakingly intricate, as each building element, stair handrail, leaf etc is separately cut out.

Painting’s relationship to performance (the subject of a current show ‘A Bigger Splash:Painting After Performance’ at Tate) was discussed in relation to Irene Rucquoi, Nicki de Saint Phalle, Aaron Young.

Nicki de Saint Phalle, Shooting Picture, 1961. She filled polythene bags with paint and enclosed them within layers of plaster against a blockboard backing. Spectators were invited to shoot at these constructions, releasing the paint. This one was shot at by Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

Aaron Young’s performance, Arc Light, uses teams of motorbike riders, whose marks are recorded on vast canvases. The canvases are cut up and displayed on the wall as artefacts. The performances are also recorded as videos, drawings, sculptures and photographs. It refers to Rauschenberg’s Automobile Tyre Print, 1951 and to Pollock’s action paintings.

Artists

Michel Majerus, Dan Hays, Damien Meade, Wade Guyton, Alistair Duncan, David Hockney, Paul Doran, Lucy Williams, Michael Craig Martin, Michael Raedecker, Franz Ackerman, Jim Isermann, Nicki de Saint Phalle, Aaron Young, Marlene Dumas, Irene Rucquoi, Lucio Fontana, Alberto Burri, Katharina Grosse, Angela De la Cruz, John Chamberlain, Ian Kiaer, Richard Tuttle, Sarah Braman, Jessica Stockholder, Isa Genzken, Matthew Richie, Pipilotti Rist, Wolf Vostell.

Posted by Madeleine Moore

Andro Wekua, from the show ‘1995’ at the Gladstone Gallery, 2010. Click here for more work by this artist.

Posted by Madeleine Moore

Painting is one of a series documenting major themes and ideas in contemporary art.

The ‘death of painting’ and its subsequent resurrection in transformed conditions is an oft-rehearsed leitmotif of the modernist era, yet from the postconceptual painting revival of the early 1980s to the present new perspectives have emerged that reopen the entire field, not only globally but historically beyond the past century. The diversity of meanings and practices signified by painting today can encompass the eclecticism associated with net-surfing and the philosophical naming as ‘painting’ of artworks that manifest no trace of paint. This is the first anthology to bring together key statements, dialogues and debates by artists and writers on art that have been building blocks of the latest era in painting’s history. Predominantly first published in magazines, journals and catalogues, these texts recontextualize polarized debates and reignite questions for the future. Tracing the story from the ‘neo’ revivals onward, this collection also ranges widely across ideas and practices of the preceding decades as they have been re-evaluated by artists and theorists in the frame of contemporary ideas.

Artists surveyed include Glenn Brown, Vija Celmins, John Currin, Marlene Dumas, Olafur Eliasson, Bernard Frize, Katharina Grosse, Andreas Gursky, Peter Halley, Gary Hume, Jutta Koether, Paul McCarthy, Suzanne McCleland, Beatriz Milhazes, Takashi Murakami, Albert Oehlen, Lari Pittman, Sigmar Polke, Gerhard Richter, Robert Ryman, David Salle, Chéri Samba, Jim Shaw, Jessica Stockholder, Philip Taaffe, Luc Tuymans, Jeff Wall and Sue Williams.

Writers include Daniel Birnbaum, Norman Bryson, Douglas Crimp, Gilles Deleuze, Sebastian Egenhofer, Hal Foster, Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe, Isabelle Graw, David Joselit, Shirley Kaneda, Geeta Kapur, Thomas Lawson, Midori Matsui, Lane Relyea, Rene Ricard, Jerry Saltz, Mira Schor, Barry Schwabsky and Adrian Searle.

Terry R. Myers is a Chicago and Los Angeles-based writer, educator and independent curator. A regular contributor since 1988 to numerous international journals, including The Brooklyn Rail, Art Review, Parkett, and Modern Painters, he is the author of Mary Heilmann: Save the Last Dance for Me (Afterall Books, 2007). He is Associate Professor of Painting & Drawing at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Softcover, 240 pages, no illustrations. ISBN 978-0-85488-188-8

Posted by Madeleine Moore